Complexity in Software: What Non-Technical Leaders Need to Know

Why Complexity Demands Different Leadership

10.12.2025, By Stephan Schwab

Software development is fundamentally complex, not merely complicated, yet most organizations manage it using approaches designed for predictable systems. Understanding this distinction — and adopting flow-based delivery over prediction-based planning — transforms how leaders fund projects, measure progress, and enable teams to navigate uncertainty while delivering value continuously.

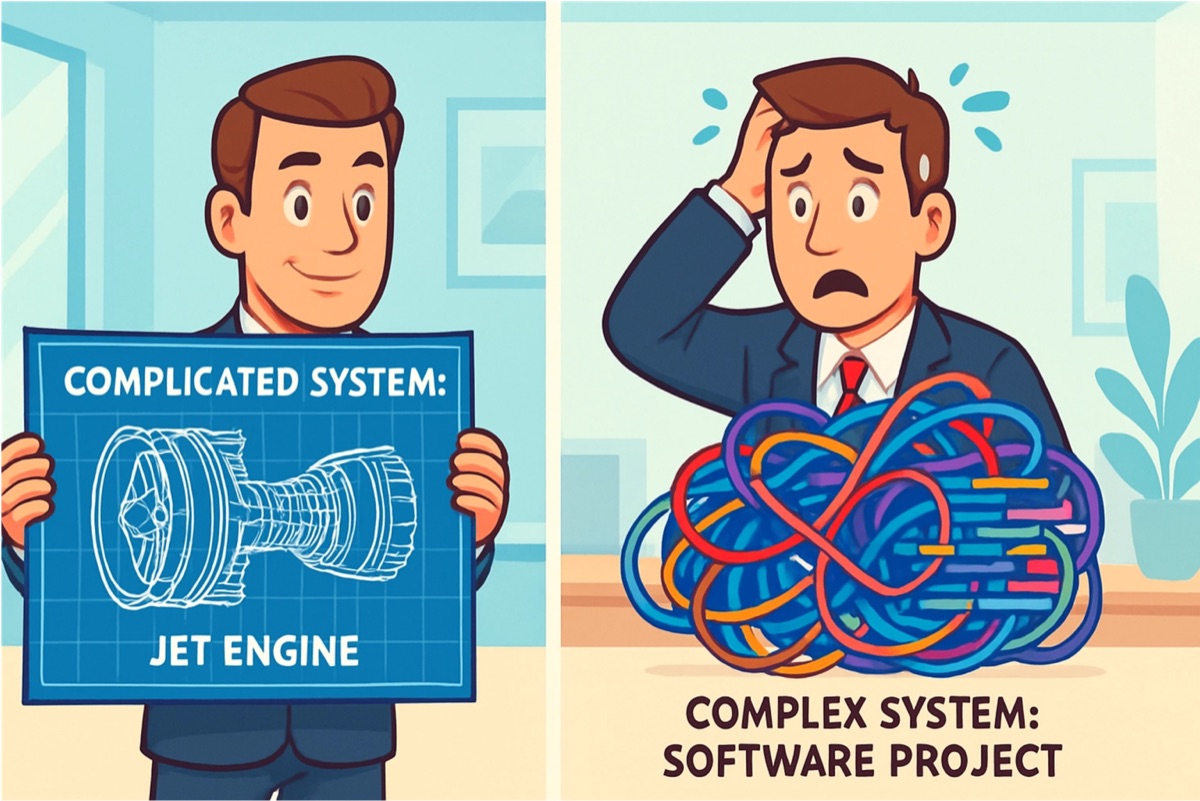

The Foundation: Complex vs. Complicated

The words “complex” and “complicated” are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation, but in systems thinking they describe fundamentally different phenomena. This distinction matters profoundly for software development.

A complicated system has many parts that interact predictably. A jet engine is complicated — thousands of components, but given the same inputs, it produces the same outputs. We can blueprint it, replicate it, and predict its behavior.

A complex system contains agents that interact in ways that produce emergent, unpredictable behaviors. The stock market, living ecosystems, city traffic — and crucially, software development — are all complex.

Why Software is Complex, Not Just Complicated

Software might appear complicated, but what makes it complex is the human dimension and emergent properties that arise from interaction.

The Porting Fallacy

Non-technical stakeholders often believe porting software to a new platform is purely complicated work — everything is known, just rewrite it in the new language. This treats software like translating a bridge blueprint from imperial to metric: tedious but mechanical. Reality proves otherwise.

When porting, you encounter: implicit knowledge buried in undocumented micro-decisions; different paradigms where old solutions become impossible or dangerous; evolved understanding that reinterprets requirements; changed context as stakeholders add “small changes”; and emergent interactions with new systems that can’t be predicted.

Six months of translation work becomes eighteen months of discovery. Not incompetence — complexity. This pattern appears throughout software development, not just porting.

Building New Features

Building features reveals similar complexity: developers interpret requirements differently, teams communicate with varying clarity, existing code constrains choices unpredictably, user needs evolve through interaction, technical decisions cascade unexpectedly, and external systems change behavior in production.

None of this can be specified upfront. User behavior reveals needs that no analysis captures. This is emergence — the whole behaves differently than its parts suggest.

The Illusion of Predictability

Why do organizations apply management approaches designed for complicated systems to complex ones?

Traditional project management emerged from domains where proven designs enable accurate estimation: bridges, automobiles, skyscrapers. Once designed, replication time is predictable.

Software doesn’t work this way. When a manager asks “How long will this take?” they expect a bridge answer. But software is more like negotiating a peace treaty or finding product-market fit. The honest answer: “We’ll discover that as we work, and show you progress along the way.”

Why Traditional Management Approaches Fail

In complicated systems, detailed upfront analysis reduces risk. In complex systems, it creates waste because reality diverges from predictions. What helps:

Short feedback loops: Deliver frequently, gather real usage data, adjust based on learning.

Empirical process control: Decide based on observation, not prediction. Track actual delivery flow.

Adaptive direction: Maintain outcome clarity while staying flexible on path. Quarterly objectives with weekly adjustments beat six-month roadmaps.

Range-based confidence: Accept “30-60 days with unknowns” instead of demanding “47 days exactly.”

Forecasts in complex systems are confidence ranges, not commitments. The further out, the wider the range.

Better than arguing about forecasts: control scope instead of predicting duration.

Focus on flow: Decompose work into smallest shippable increments. Ship minimal but valuable versions in days, gather data, decide next. This shifts conversation from “When done?” to “What ships this week?”

Shipping every 3-5 days means ~15-20 increments per quarter — that’s your velocity. This requires technical practices making small changes routine: automated verification, conflict-free integration, ceremony-free deployment.

The benefit: discover you built the wrong thing in weeks, not months. Risk decreases with each release instead of accumulating toward big-bang deployment.

How to Navigate Complexity: Ship Small, Learn Fast

The most effective response: work in small increments delivered to actual users. This transforms complexity into manageable, complicated problems.

Identify the smallest valuable piece, build to production quality, ship, measure user interaction, learn, decide next. User needs and technical constraints reveal themselves through interaction, not speculation. Essential features go unused; overlooked details drive adoption.

Breaking Down Complexity

Proven techniques decompose complex ideas into manageable increments:

Vertical slicing: Build one complete capability end-to-end, not layers. “User logs in with email” — not “authentication database schema.”

User story mapping: Identify minimal viable path through user journey. Everything else becomes optional.

Walking skeleton: Thinnest implementation connecting all layers, then add incrementally. Surfaces integration risks early.

Feature toggles: Deploy code inactive, enable for user subsets to gather evidence before full rollout.

Hypothesis-driven: Frame increments as testable beliefs. Build minimum to test, measure, decide.

These transform “What should we build?” (complex) into “How do we implement this?” (complicated). Complicated problems yield to skill. Complex problems need experimentation.

The Role of Technical Excellence

These techniques only work if teams can safely ship small changes frequently. This demands practices that become second nature:

Test-Driven Development (TDD): Verifies each increment during building. Not bureaucracy — confidence when integrating dozens of daily changes. Skipping TDD accumulates debt that prevents iteration.

Continuous Integration (CI): Multiple daily merges with automated verification surface problems in hours, not weeks. Essential because complexity lies in how pieces interact.

Continuous Deployment (CD): Automated pipelines deploy multiple times daily, eliminating ceremony and risk. Manual coordination forces large, risky batches.

Evolutionary architecture: Systems that change incrementally, not through rewrites. Extension and composition, not rigid hierarchies.

Without these, you’re forced into large batches — not because it’s better, but because your practices can’t support anything else. Wanting business agility without technical excellence is like wanting air travel while refusing to maintain engines.

The Hidden Cost of Ignoring Complexity

Treating software as complicated creates predictable dysfunctions:

False precision: Six-month forecasts treated as commitments. When reality diverges, blame replaces learning.

Premature optimization: Locked-in decisions before understanding the problem. Expensive rework or systems serving theoretical needs.

Micromanagement: Controlling every detail removes teams’ ability to adapt to learning.

Risk accumulation: Avoiding frequent deployment defers complexity’s reveal. When it arrives — often before deadlines — accumulated risk explodes.

What Non-Technical Leaders Can Do

Understanding complexity doesn’t abandon accountability. It adapts leadership:

Ask “What did you learn?” not “Did you follow the plan?” Learning velocity matters more than prediction adherence.

Value visible progress: Working software deployed to production tells more than Gantt charts and task percentages.

Invest in fast feedback: Support automated testing, continuous integration, and telemetry.

Fund incrementally: Smaller increments tied to validated outcomes create pivot points based on evidence.

Trust technical judgment on how: Maintain clarity on what and why. Teams need autonomy to navigate complexity.

The Bridge Between Worlds

Leadership changes require technical teams to meet halfway. The understanding gap creates friction: developers feel dismissed when leaders demand impossible certainty; leaders feel frustrated by unpredictability.

The bridge requires mutual adaptation:

- Technical teams communicate risk, value, and options — not minutiae

- Business leaders accept that direction matters more than detailed roadmaps

- Both agree on reality-based measurements: delivery frequency, production stability, validated outcomes

Complexity isn’t an excuse for lack of discipline. It demands different disciplines — empirical over predictive, adaptive over prescriptive.

Building Organizational Intelligence

Systems that surface empirical evidence naturally bridge the gap. Tools like Caimito Navigator help teams maintain daily logbooks — capturing blockers, progress, learning — then synthesize weekly intelligence summaries for leadership.

This creates shared visibility without status meetings. Both parties work from the same factual foundation. When friction appears, leadership responds: removing impediments, adjusting scope, or embedding expertise. Complexity becomes visible and navigable.

Moving Forward

When projects feel unpredictable or teams push back on long-term commitments, ask:

- Are we deciding based on production data or months-old predictions?

- Do we have fast feedback loops revealing what works?

- Are we treating forecasts as ranges or guarantees?

- Have we created space for emergence or are we controlling every variable?

Complexity isn’t a problem to solve — it’s a reality to navigate. Organizations that accept this build better products faster with less friction. Those treating software as merely complicated will repeat the same frustrations.

The difference between complex and complicated isn’t semantic. It’s working with reality versus fighting it.

Contact

Let's talk about your real situation. Want to accelerate delivery, remove technical blockers, or validate whether an idea deserves more investment? Book a short conversation (20 min): I listen to your context and give 1–2 practical recommendations—no pitch, no obligation. If it fits, we continue; if not, you leave with clarity. Confidential and direct.

Need help? Book a 20-min conversation—practical advice, no pitch. Or email: sns@caimito.net

Prefer email? Write me: sns@caimito.net