Grace Hopper: The Compiler That Changed Everything

6 min read

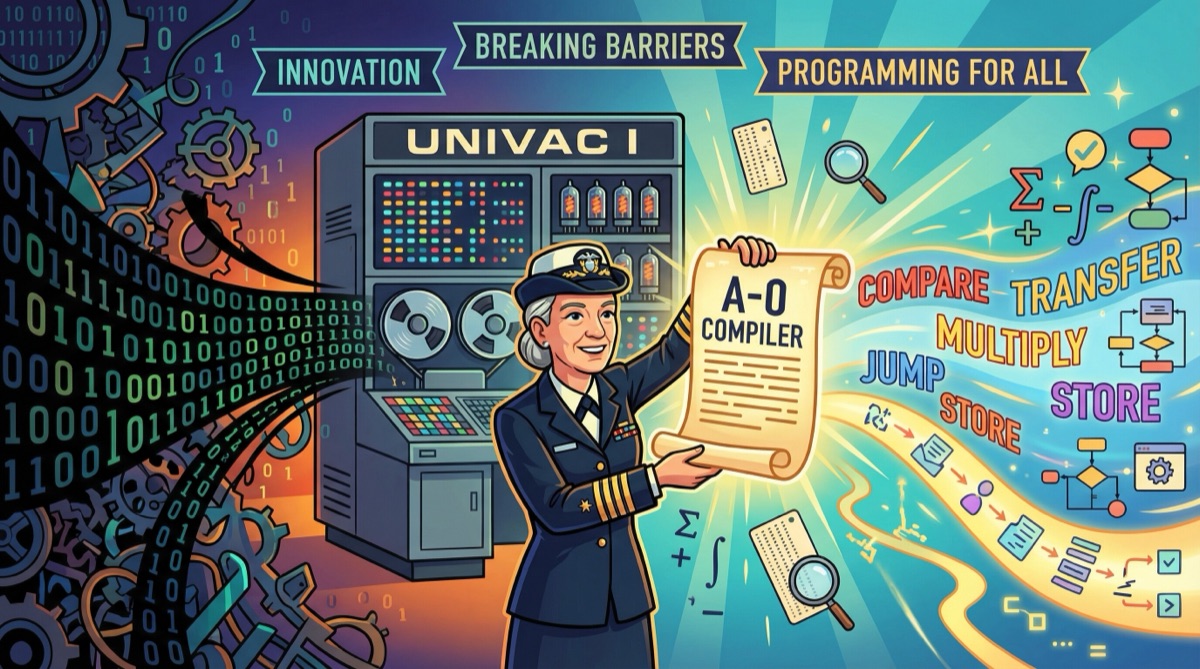

She Made Machines Understand Words

21.01.2026, By Stephan Schwab

Before Grace Hopper, programming meant thinking in binary. Her invention of the compiler didn't just make programming easier — it made programming possible for everyone who wasn't a mathematician. The abstraction she pioneered remains the foundation of every line of code written today.

The Problem Nobody Wanted to Solve

In 1952, programming a computer meant writing sequences of numbers. Machine code. Ones and zeros, or if you were lucky, hexadecimal values that represented ones and zeros slightly more compactly. Every instruction, every memory address, every calculation — numbers.

The programmers of that era were mathematicians. They had to be. The cognitive overhead of translating human intent into numeric sequences required a particular kind of mind. Most people looked at programming and saw an impenetrable wall.

Grace Hopper looked at the same wall and asked a different question: Why should humans learn to think like machines when we could teach machines to understand humans?

Her colleagues thought she was crazy. Computers do arithmetic, they said. You can’t make a computer understand words. The machine doesn’t know English.

She built it anyway.

The A-0 System: Proof That Abstractions Work

In 1952, Hopper created the A-0 System for the UNIVAC I. It wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t fast. What it did was revolutionary: it took mathematical notation that humans could read and translated it into machine code that computers could execute.

A compiler. The first one. The concept that you could write in one language and have a machine automatically translate it to another.

The reaction from the computing establishment was predictable. They didn’t believe her. For three years, she demonstrated her compiler and was told it couldn’t work — while they watched it work. The resistance wasn’t technical. It was psychological. Programmers had invested enormous effort in learning to think in machine code. They had made themselves indispensable through an arcane skill. A compiler threatened that position.

Sound familiar?

From A-0 to FLOW-MATIC to COBOL

Hopper wasn’t satisfied with making programming easier for mathematicians. She wanted to make it accessible to business people who needed to solve business problems.

In 1958, she led the team that created FLOW-MATIC, the first programming language to use English-like syntax. Not mathematical notation. Actual words. COMPARE, TRANSFER, MULTIPLY. Instructions that a business manager could read and understand.

The computing priesthood was horrified. Real programmers don’t use English, they insisted. This will make programming too easy. It will let the wrong people in.

Hopper’s response was characteristic: “It is easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.” She built it anyway. FLOW-MATIC directly influenced COBOL, which by 1970 was the most widely used programming language in the world.

Billions of lines of COBOL are still running today. In banks. In insurance companies. In government systems. Code written in a language designed to be readable by non-programmers, still processing transactions sixty years later.

The Abstraction That Keeps Giving

The compiler was more than a tool. It was a proof of concept. It demonstrated that abstraction — hiding complexity behind simpler interfaces — was not just possible but essential for the growth of computing.

Every programming language you use today exists because Grace Hopper proved that machines could translate human-readable code into machine instructions. Python, JavaScript, Rust, Go — all of them depend on compilers or interpreters that trace their conceptual lineage back to A-0.

The principle extends beyond languages. Every framework that hides complexity. Every library that provides a simpler interface to a harder problem. Every API that abstracts away implementation details. They all embody the same insight: humans shouldn’t have to think like machines.

When someone tells you that “real programmers” don’t use frameworks, or that you should understand everything happening at the machine level before you’re allowed to use higher-level tools, they’re echoing the same resistance that Hopper faced in 1952. The gatekeeping hasn’t changed. Only the abstraction layer being defended has shifted.

The Organizational Insight

Hopper’s three years of demonstrating a working compiler to people who insisted it couldn’t work tells us something important. The barriers to progress in software are rarely technical. The A-0 compiler worked. The resistance was human.

This pattern repeats constantly. Test-driven development works. Continuous integration works. Trunk-based development works. The evidence is overwhelming. Yet organizations resist, not because the techniques don’t work, but because adopting them requires changing how people think about their work.

Hopper didn’t just build a compiler. She spent years evangelizing the concept, demonstrating it, convincing skeptics one by one. The technical achievement was necessary but not sufficient. The human work — changing minds, overcoming institutional inertia — was equally important.

Permission and Forgiveness

Her famous quote — “It is easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission” — wasn’t about being reckless. It was about recognizing that gatekeepers often protect their positions rather than the organization’s interests. Sometimes the only way to prove something works is to build it and show results.

This doesn’t mean ignoring legitimate concerns. It means recognizing when “concerns” are actually fear of change dressed in technical language. Hopper’s compiler didn’t threaten the machines. It threatened the monopoly of a small group of specialists.

Every time someone tells you that your approach won’t work — without trying it — ask yourself whether they’re protecting technical integrity or professional territory. The answer is usually obvious.

The Standard That Emerges

COBOL became a standard not because a committee decreed it, but because FLOW-MATIC and similar languages demonstrated the value of the approach. The standard followed the practice, not the other way around.

Hopper understood this. She built working systems first. The standardization — COBOL, developed by a committee she participated in — came after the concept had proven itself in production. The standard codified what worked, rather than specifying what might work theoretically.

This remains good advice. Build something that works. Demonstrate value. Let the standard emerge from practice. The alternative — designing standards before implementation — produces specifications that satisfy committee politics but fail in reality.

What She Teaches Us

Grace Hopper’s contribution to software development wasn’t just the compiler. It was the demonstration that:

Abstraction is strength, not weakness. Every layer of abstraction that hides complexity and exposes simpler interfaces makes software more accessible and more powerful.

Working code beats theoretical arguments. Three years of demonstrating a working compiler eventually overcame resistance that no amount of argument could have defeated.

Gatekeeping is about power, not quality. The people who insist that programming should remain difficult are protecting their position, not the craft.

Standards follow practice. Build what works, prove its value, and the standard will emerge.

Human change is harder than technical change. The compiler was the easy part. Convincing the industry to use it was the real work.

The next time you use a high-level programming language — any of them — you’re building on the foundation Grace Hopper laid in 1952. Not just technically, but conceptually. She proved that we don’t have to think like machines. We can teach machines to understand us instead.

That insight changed everything.

Contact

Let's talk about your real situation. Want to accelerate delivery, remove technical blockers, or validate whether an idea deserves more investment? I listen to your context and give 1-2 practical recommendations. No pitch, no obligation. Confidential and direct.

Need help? Practical advice, no pitch.

Let's Work Together