When Discovery Collides with Process

Technical teams constantly discover better ways of working — through practice, through new tools, through the kind of...

12 min read

09.01.2026, By Stephan Schwab

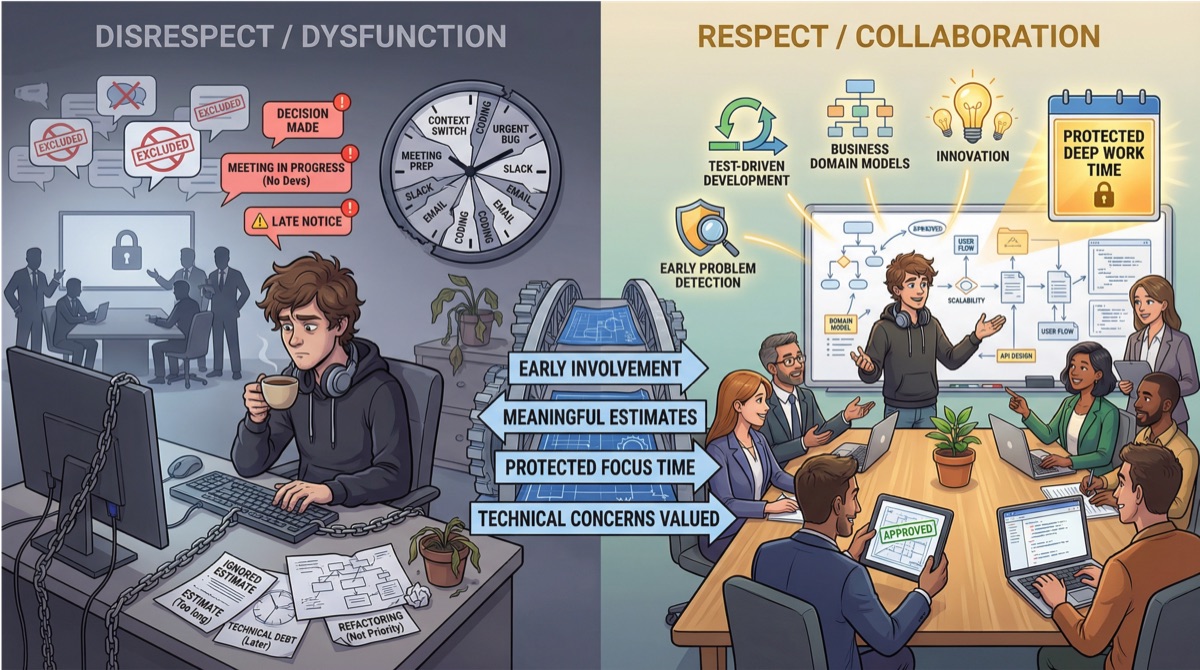

Respect for software developers is not a perk — it is a prerequisite for building anything worth using. Most developers are introverts who have no interest in office politics; they simply want to solve problems well. Through rigorous practices like test-driven development, they often understand the business more deeply than anyone realizes. You cannot demand their best effort, but when they believe in the mission, they will give it freely. Organizations that treat this expertise with genuine respect get cleaner code, earlier problem detection, and innovation that no specification could capture.

There is a quiet epidemic in software organizations. Developers are hired for their expertise, then systematically excluded from the decisions that shape their work. They are expected to estimate tasks they had no part in defining, implement solutions designed by people who will never touch the code, and meet deadlines set without their input. Then, when things go wrong, they are asked what went wrong — as if they had been steering the ship all along.

This is not respect. This is using people as an extension of a keyboard.

The irony is visible in every frustrated executive who wonders why their teams lack initiative. You cannot hire expertise and then ignore it. You cannot recruit problem-solvers and then hand them solutions. The pattern defeats itself.

The cost of this pattern is enormous, but it rarely appears on any dashboard. It shows up in the best developers leaving for companies that value their judgment. It shows up in systems that technically work but are painful to change. It shows up in estimates that everyone knows are fiction but nobody is allowed to say so. And it shows up in the slow, grinding disengagement of people who once cared deeply about their craft.

Respect for developers does not mean giving them whatever they want. It does not mean avoiding hard conversations about priorities, deadlines, or trade-offs. It means something more fundamental: treating them as professionals whose perspective has value, whose time has limits, and whose expertise was acquired through years of deliberate practice.

In practice, this looks like:

Including developers in problem definition, not just solution delivery. The difference between a developer who understands why something matters and one who is handed a specification is the difference between engaged problem-solving and compliant implementation. Developers who understand the business context make better decisions at every level of the code.

Asking for estimates and listening to the answers. Many organizations have ritualized estimation into a performance where developers say numbers and managers nod, then set the actual deadlines based on other factors. This teaches developers that their judgment does not matter — a lesson they remember when asked to flag technical risks later.

Protecting focused time. Context switching is not a minor inconvenience for software development; it is an architecture-level problem. A developer interrupted four times in a morning does not lose four small blocks of time — they lose the ability to hold complex systems in their head long enough to reason about them. Organizations that respect this fact structure meetings, communication, and expectations accordingly.

Taking technical concerns seriously. When developers raise concerns about architecture, technical debt, or unrealistic timelines, they are not being obstructionist. They are offering information that most organizations desperately need and systematically ignore. The proper response is to understand the concern, weigh it against other factors, and make a decision — not to dismiss it as “not understanding the business.”

Most software developers are introverts. This is not a stereotype — it is a consistent finding across decades of personality research in technical fields. Introversion is not shyness or social anxiety; it is a preference for depth over breadth, for thinking before speaking, for processing internally before expressing externally.

This has profound implications for how developers communicate, especially in meetings.

In a typical meeting, developers may appear quiet or disengaged. They are not. They are listening, evaluating, and forming views they may or may not share depending on whether the environment feels safe. When they do speak up forcefully — interrupting, raising their voice, or pushing back hard — it is rarely because they have suddenly become assertive. It is usually because they feel unheard, cornered, or witness to a decision so misguided they cannot stay silent.

Organizations that interpret this quietness as lack of opinion, and then interpret rare outspokenness as attitude problems, have the dynamic exactly backwards. The quiet is normal. The loud is a signal — often the last one before disengagement.

There is another trait worth understanding: most developers have little interest in controlling a narrative or playing office politics. They are not competing to be seen as the person with the best idea in the room. They are not angling for credit or positioning themselves for the next reorg. They simply want to solve the problem well and move on to the next one.

This disinterest in political maneuvering is often misread. Executives accustomed to environments where everyone is managing perception may assume developers are naive, or that their apparent indifference to optics means they do not care about outcomes. The opposite is true. Developers care intensely about outcomes — they just measure success by whether the system works, not by who gets credit for it.

When organizations treat this apolitical orientation as a weakness to exploit rather than a strength to protect, they poison the well. Developers who are forced into political games do not become better politicians; they become disengaged engineers.

This communication pattern and political disinterest are aspects of a deeper issue: many organizations do not invest in understanding the people who build their software.

One of the strangest dynamics in software organizations is the asymmetry of expected understanding. Developers are frequently told they need to “understand the business” — as if they were somehow disconnected from it. But developers who practice test-driven development, who model business rules in code, who translate domain concepts into working systems — these developers often understand the business more deeply than anyone realizes.

The act of writing tests forces a developer to confront every edge case, every exception, every unstated assumption. What happens when a customer cancels mid-transaction? What if an account has multiple owners with different permissions? What does “expired” mean when the product crosses time zones? These are not technical questions. They are business questions that developers must answer precisely, in code, or the system fails.

Organizations that encourage developers to “learn about the business” have it backwards. Developers who do rigorous work already know the business — often better than the people who handed them requirements. The question is whether anyone asks them what they have learned. The insight sitting in the heads of your development team is an untapped resource. They have seen where the specifications contradict themselves, where the edge cases reveal unstated policies, where the domain model breaks down under real conditions.

Yet this expertise is rarely solicited. Instead, developers are expected to absorb business context quietly and implement what they are told. The asymmetry runs in the wrong direction: developers are treated as consumers of business knowledge rather than contributors to it.

The reverse expectation is curiously absent as well. Executives and product managers are rarely expected to develop even a basic understanding of software development. Technical complexity is treated as someone else’s problem, a black box that should simply produce features on demand.

This double asymmetry creates a power imbalance that undermines respect. Developers must understand the business but are not asked for their insight; meanwhile, the organization’s fundamental assumptions about how software works remain unexamined. The relationship becomes extractive rather than collaborative.

The most effective organizations bridge this gap in both directions. Leaders learn enough about software development to ask good questions, recognize reasonable trade-offs, and understand why some things are harder than they appear. And they treat developers as sources of business insight, not just recipients of requirements. This does not require learning to code. It requires genuine curiosity and the humility to recognize that expertise deserves understanding, not just deployment.

When that curiosity is absent, small frictions accumulate into something more damaging.

Disrespect rarely announces itself. It accumulates in small moments: the meeting where a developer’s concern was brushed aside, the deadline set without consultation, the architecture decision made by someone who will not maintain the result, the performance review that valued hours logged over problems solved.

Each incident is survivable. In aggregate, they create an environment where the best developers leave — not always for more money, but for organizations that value what they know. What remains is a workforce that has learned to protect themselves through compliance: do what is asked, no more and no less, and save your real thinking for somewhere it might matter.

This protective withdrawal becomes most visible when the organization needs something it cannot command.

One of the clearest indicators of respect — or its absence — is how an organization handles crunch time. Every software project has moments of genuine urgency: a critical bug in production, a competitive deadline, an unexpected opportunity that requires fast movement. Developers understand this. They have been through it before.

Here is what organizations often fail to grasp: you cannot demand this kind of effort. You can require people to be present, but you cannot require them to bring their full capability, their creative problem-solving, their willingness to push through walls. That can only be given, and it is given when people believe the mission matters and that their contribution is valued.

Developers who respect their organization and feel respected in return will work weekends to ship something important. They will stay late to fix a critical issue. They will think about hard problems in the shower and arrive Monday with solutions. This is not because they are told to — it is because they care.

But extract that effort through pressure, guilt, or normalized overwork, and you get something that looks similar but is fundamentally different. You get hours logged, not problems solved. You get presence without engagement. And you burn through goodwill that takes years to rebuild.

This is the hidden cost of treating developers as resources rather than professionals: you get exactly what you measure and specify — and nothing beyond. The small improvements, the edge cases caught early, the architectural foresight that prevents next year’s crisis: these come from people who care, and caring requires a reason.

Organizations that struggle with software delivery often look for process solutions: better project management, more detailed specifications, tighter controls. Sometimes these help. But often the problem is simpler and harder to fix. The people who build the software have stopped believing that their judgment matters, and they are acting accordingly.

The good news is that this dynamic can be reversed — not through slogans, but through structure.

Changing this pattern requires structural changes that demonstrate, through repeated experience, that developer expertise is valued.

Involve developers early. When a new initiative is being shaped, include developers in the conversation before the solution is determined. Their early input often prevents expensive mistakes and creates ownership that no amount of later explanation can replicate.

Make estimates meaningful. If developers provide estimates, treat those estimates as real information. If deadlines must be set differently, be honest about why — and acknowledge that the gap between estimate and deadline represents risk the organization is choosing to accept.

Protect deep work. Audit how developers actually spend their time. If the best engineers are spending more time in meetings than in focused development, something is structurally wrong. Consider meeting-free days, async-first communication, and expectations that protect rather than fragment attention.

Create real feedback loops. Developers should see what happens when their software reaches users. This is not about blame when things go wrong — it is about connection between effort and outcome. When developers see real usage data and user behavior, their decisions become better informed and more motivated.

Take technical concerns seriously. When developers raise concerns about technical debt, complexity, or timeline risk, treat these as valuable business intelligence. You may still decide to proceed as planned, but the decision should be explicit and informed — not a reflexive dismissal.

Organizations that genuinely respect their developers do not just retain talent better — they get different results. Code is cleaner because developers take pride in their work. Problems are flagged earlier because raising concerns is rewarded, not punished. Innovation happens naturally because people are engaged enough to see opportunities that no specification would capture.

This is not idealism. It is practical recognition that software development is knowledge work performed by humans, and those humans respond to how they are treated. Respect is not a cost center. It is the foundation of every system that works well and keeps working.

The question for any organization is simple: are you treating your developers as professionals whose judgment you value, or as sophisticated keyboards you are trying to operate more efficiently? The answer shows up in the software — eventually, it shows up everywhere.

I was born in late 1968. When Borland released Turbo Pascal in 1983, I was fourteen years old and already teaching week-long classroom courses to adults — professionals who struggled to grasp basic programming concepts that seemed obvious to me. These were intelligent people, successful in their own fields, sitting in a room being taught by a teenager.

Nobody questioned whether I understood the material. What mattered was whether I could help them understand it.

Software has always been like this. Expertise in this field does not correlate with age, seniority, or organizational rank. A twenty-three-year-old developer may understand a system better than the executive who commissioned it. A junior hire may spot the flaw that senior architects missed. The person closest to the code often knows things that the person furthest from it cannot see.

Organizations that respect developers understand this. They do not assume that hierarchy equals insight. They ask questions of people who have answers, regardless of title or tenure. And they recognize that in a field where a teenager can teach adults, the traditional markers of authority may not apply.

Respect the expertise. It does not always come from where you expect.

Let's talk about your real situation. Want to accelerate delivery, remove technical blockers, or validate whether an idea deserves more investment? I listen to your context and give 1-2 practical recommendations. No pitch, no obligation. Confidential and direct.

Need help? Practical advice, no pitch.

Let's Work Together