Governing Legacy Modernization: Oversight for the Strangler Fig

The Death of Big-Bang Replacement

27.01.2026, By Stephan Schwab

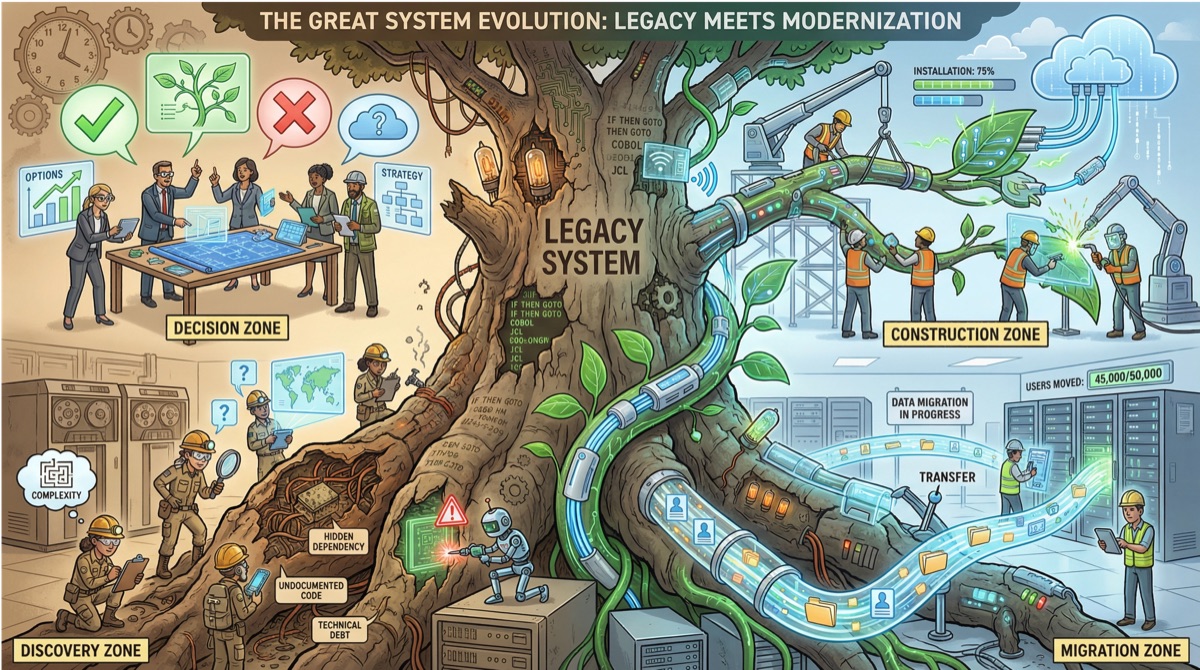

Legacy modernization rarely happens in neat phases anymore. The strangler fig pattern — incrementally replacing pieces of a legacy system while both systems run — means discovery, decision-making, construction, and migration happen concurrently across different slices. Governing this requires tracking multiple work streams simultaneously, each at a different stage of maturity, rather than moving the whole project through sequential gates.

Why Sequential Phases Don’t Reflect Reality

Traditional project thinking imagines modernization as a sequence: first understand the legacy system, then decide what to build, then build it, then migrate. Each phase completes before the next begins. Governance checkpoints mark the transitions.

This mental model made sense when systems were replaced in big-bang cutovers — one weekend, everything switches. But big-bang replacements are increasingly rare, and for good reason. They concentrate risk into a single moment. They require understanding the entire legacy system before replacing any of it. They demand that the new system be complete before anyone uses it.

The strangler fig pattern works differently. You identify a slice of functionality, understand that slice, build its replacement, migrate its users, and decommission that piece of the legacy system — while the rest continues running. Then you do it again with another slice.

This means at any given moment, different slices are at different stages. You’re still discovering some parts of the legacy system while you’re already migrating users off other parts. Governance that assumes sequential phases can’t see this clearly.

Four Concurrent Work Streams

Rather than phases, think of modernization as four types of work happening concurrently, each applying to different slices of the system at any given time.

Discovery Work

Understanding what the legacy system actually does. This is

craft work: investigation, hypothesis, verification. Legacy systems accumulate behavior over decades. Documentation describes intent, not reality. The developers who understood the quirks have departed.

Discovery happens throughout the project, not just at the beginning. When you start working on a new slice, you discover things about that slice. When migration reveals unexpected behavior, you’re doing discovery. When users report that the new system handles something differently, discovery explains why.

Governance questions for discovery work:

- Which slices are we currently investigating?

- What have we learned that surprised us?

- Are we talking to the people who actually use each slice?

- Is discovered behavior being documented for future slices?

- Are we finding things that affect slices we thought we understood?

Decision Work

Choosing what the replacement should do. Not every legacy behavior deserves replication. Some behaviors are essential business logic; others are accidental complexity from old constraints; others are bugs that users have worked around for so long they’ve become expectations.

Decision work happens for each slice as you prepare to build its replacement. It may also happen when construction reveals that earlier decisions were wrong, or when migration surfaces behaviors no one anticipated.

Governance questions for decision work:

- Which slices have pending decisions?

- Who is involved in these decisions? Is the business represented?

- What tradeoffs are we making, and are they explicit?

- Are we distinguishing “how it works” from “how it should work”?

- Are decisions being documented so future slices can learn from them?

Construction Work

Building the replacement components. Once you understand a slice and have decided what its replacement should do, construction often follows trade patterns — established approaches, standard frameworks, familiar architectures. The novelty was in discovery and decision; the building is execution.

Multiple slices may be under construction simultaneously. Some may be nearly complete; others just starting. Governance needs to track each without assuming they’re all at the same stage.

Governance questions for construction work:

- Which slices are under construction?

- For each, can the team estimate remaining work with confidence?

- Are slices being built in a way that enables incremental migration?

- Are integration tests validating behavior against real legacy data?

- Is construction revealing gaps in earlier discovery or decisions?

Migration Work

Moving users and data from the legacy slice to its replacement. This is often the hardest work — not technically, but operationally. Running systems in parallel, synchronizing data, shifting traffic gradually, handling edge cases where old and new behave differently.

Migration work may surface problems that send you back to discovery, decision, or construction. A slice you thought was complete turns out to handle a case you didn’t know about. Users report behavior they depended on that the replacement doesn’t provide. The integration between the new slice and remaining legacy components doesn’t work as expected.

Governance questions for migration work:

- Which slices are in migration?

- What percentage of traffic/users has shifted to each new slice?

- What problems have emerged, and how are they being addressed?

- Are we on track to decommission the legacy piece?

- What’s blocking full migration for each slice?

Governing the Portfolio of Slices

Effective modernization governance tracks a portfolio of slices, each at its own stage. This looks less like traditional project oversight and more like portfolio management.

A useful governance view shows:

| Slice | Discovery | Decisions | Construction | Migration | Blocking Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billing | Complete | Complete | Complete | 60% migrated | Data sync latency |

| User Auth | Complete | In progress | Not started | — | Awaiting security review |

| Reporting | In progress | — | — | — | Key user on leave |

| Inventory | Not started | — | — | — | Depends on Billing |

This view reveals several things traditional project tracking misses:

Dependencies between slices. Some slices can’t start until others complete. Some share components. Governance can see these relationships.

Where work is stuck. A slice that’s been “in progress” on decisions for months needs attention. A slice that’s 40% migrated and hasn’t moved in weeks has a problem.

Resource allocation. If too many slices are in construction and nothing is migrating, teams may be avoiding the hard operational work. If everything is in discovery and nothing is being built, investigation may have become an excuse for inaction.

Actual progress. Migrated slices with decommissioned legacy pieces represent real progress. Everything else is work in progress.

When Work Streams Interact

The concurrent nature of strangler fig modernization means discoveries in one stream affect work in others.

Discovery reveals that a decision was wrong. A slice under construction turns out to need capabilities you decided not to include. Do you revise the decision, extend the slice, or accept a gap?

Construction exposes incomplete discovery. Building the replacement surfaces legacy behaviors no one knew about. Do you pause construction, document and decide quickly, or build what you know and handle the rest later?

Migration proves the replacement inadequate. Users in production find problems that testing missed. Do you roll back, fix forward, or run both systems longer?

Governance that treats any backwards movement as failure creates incentives to hide problems. Governance that accepts iteration while monitoring for genuine stalls enables teams to respond to reality.

Signals Across Work Streams

Rather than tracking percentage complete, effective governance monitors signals that reveal actual health.

Healthy Signals

- Slices are moving through stages at a reasonable pace — not stuck indefinitely in any stage.

- Discovered surprises lead to explicit decisions, not silent scope creep.

- Construction velocity is roughly consistent once slices reach that stage.

- Migration percentages increase over time; slices eventually reach 100% and legacy pieces turn off.

- Problems surface early and get addressed; they don’t accumulate silently.

Warning Signals

- Multiple slices stuck in discovery with no decisions being made.

- Decisions being made without business involvement.

- Construction happening but no slices reaching migration.

- Migration stalled at partial percentages — parallel running becoming permanent.

- Teams reporting green status while nothing actually moves to production.

- Discovery work expanding to slices not yet scheduled, suggesting avoidance of harder slices.

The Budget Question

“How much will this cost?” is hard to answer for strangler fig modernization because you’re not building a single thing — you’re replacing a system piece by piece.

Approaches that work:

-

Per-slice budgeting. Estimate and fund each slice separately. Early slices inform estimates for later similar slices. Variation averages out across the portfolio.

-

Burn rate over time. Rather than asking “how much total,” ask “how much per month” and “for how long.” Track whether burn rate is producing proportional migration progress.

-

Value-based prioritization. Not all slices are equally valuable. Prioritize slices that relieve the most pain, reduce the most risk, or enable the most opportunity. Stop when the remaining legacy pieces aren’t worth replacing.

Approaches that fail:

-

Demanding total cost upfront. You don’t know how many slices exist until you start. You don’t know how hard each slice is until you work on it. Total estimates made early will be wrong.

-

Treating all slices as equivalent. Some slices are simple; others are deeply entangled. Governance that assumes uniform effort misunderstands the work.

-

Waiting until everything is “done.” With strangler fig, you can stop when remaining slices aren’t worth the effort. Governance should ask “is this slice worth it?” not just “is it done?”

Management Frameworks Offer Nothing for the Actual Work

Organizations often reach for familiar management frameworks when governing modernization. This is understandable — executives want structure they recognize. But here’s an uncomfortable truth: management frameworks have nothing to offer for the actual software development work. They don’t help developers understand legacy code, make architectural decisions, write better tests, or migrate users safely.

SAFe, LeSS, PMI, PRINCE2, and similar frameworks concern themselves with organizational coordination, resource allocation, reporting structures, and stakeholder communication. These are legitimate concerns — but they are entirely separate from software development. No management framework teaches you how to refactor a legacy codebase, design a strangler facade, validate behavior equivalence, or handle data migration. No planning ceremony produces better code. No project charter improves your test coverage.

This matters for legacy modernization because the actual difficulty lies entirely in the technical work: understanding what the legacy system really does, deciding what behavior to preserve, building replacements that work correctly, and migrating without disrupting users. Management frameworks are silent on all of this.

What management frameworks address:

- How to report progress to stakeholders

- How to coordinate multiple teams

- How to allocate budgets across initiatives

- How to structure governance committees

- How to escalate decisions

What management frameworks don’t address — and can’t:

- How to investigate undocumented legacy behavior

- How to design replacements that can run alongside legacy systems

- How to test that new and old produce equivalent results

- How to migrate users incrementally without data loss

- How to handle the edge cases that only surface in production

Approaches that actually help the work:

Kanban-style visualization works for tracking slices across stages — but this is a visualization technique, not a management framework. Teams benefit from seeing work items move through columns with WIP limits. The board doesn’t tell you how to do the work; it helps you see where work is stuck.

Cynefin (Dave Snowden) helps governance understand why different work streams need different approaches — discovery work lives in the complex domain; construction work is complicated. But again, this is a sensemaking tool for choosing approaches, not a prescription for executing them.

Real Options thinking treats each slice as an option — investing in discovery buys the option to build. This helps with prioritization decisions, not with the actual building.

The pattern is clear: useful approaches help you see, decide, or prioritize. None of them help you actually do the technical work. That requires engineering skill, domain knowledge, and hands-on experience — none of which come from management frameworks.

The danger:

When organizations invest heavily in management framework adoption, they often believe they’ve addressed the modernization challenge. They haven’t. They’ve addressed the coordination and reporting challenge — which is real, but much smaller than the technical challenge. A perfectly governed project with inadequate technical capability will still fail. An ungoverned project with excellent technical execution might succeed despite the chaos.

The Patience for Incremental Progress

Strangler fig modernization produces incremental value — each migrated slice is a piece of legacy system that no longer needs maintenance, a piece of technical debt retired, a group of users on a better system. But it doesn’t produce dramatic milestones.

Executives accustomed to big project launches may find this unsatisfying. There’s no ribbon-cutting moment — just the gradual dimming of the legacy system’s lights. Governance that demands visible milestones may create pressure to batch work artificially, losing the risk reduction that incremental migration provides.

The organizations that modernize successfully are those where governance values sustainable progress over theatrical milestones. They celebrate each decommissioned legacy piece. They trust that the system is getting better even when there’s no single moment to point to. They understand that software development includes significant design work — and that design work applied slice by slice, with learning between slices, produces better results than attempting to design everything upfront.

The legacy system took years to build and decades to evolve. The strangler fig will take time too — but it will produce value along the way, not just at the end.

Contact

Let's talk about your real situation. Want to accelerate delivery, remove technical blockers, or validate whether an idea deserves more investment? Book a short conversation (20 min): I listen to your context and give 1–2 practical recommendations—no pitch, no obligation. If it fits, we continue; if not, you leave with clarity. Confidential and direct.

Prefer email? Write me: sns@caimito.net